The following violins bring alive stories and lessons from the past. They are monuments to the family Amnon Weinstein never knew, and to the 6 million Holocaust victims who cannot speak for themselves. These instruments are like a forest of sound, violins that, when played, speak for all of them. These are the Violins of Hope.

The Wagner Violin

1936

This fine, high-quality instrument belonged to a member of the Palestine Orchestra, created in 1936 by Bronisław Huberman. Along with other violins in this collection, it played a key role in the formation of this historic ensemble, which in 1948 was renamed the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Most members of the Palestine Orchestra were first-rate musicians who lost their jobs when the Nazis came to power in 1933 and began enforcing racial laws in Germany.

When the war ended, there was a boycott of German goods in Israel—so much so that the word “Germany” was banned on the radio. Musicians then refused to play on German-made instruments and many approached Moshe Weinstein asking him to buy their violins. Many even threatened to break or burn their instruments. Weinstein bought every instrument as for him any violin transcended war and evil in value. Yet he knew he could never sell them, thus these instruments have become part of the Violins of Hope. This story is told in greater detail in Chapter 1 of James A. Grymes’ Violins of Hope.

The Auschwitz Violin

Made in the workshop of Schweitzer in Germany, c. 1850

This instrument was originally owned by an unnamed inmate who performed in the men’s orchestra at the concentration camp in Auschwitz—and survived. Abraham Davidowitz, a Jew who fled from Poland to Russia in 1939, encountered the instrument upon returning to postwar Germany to assist Jewish survivors living in displaced people’s camps near Munich. One day, a former inmate — sad and impoverished—approached Abraham and offered him the violin.

Abraham paid $50 for the violin, hoping that his young son, Freddy, would play it when he was older. Many years later, Freddy heard about the Violins of Hope project and donated this instrument to be fully restored. Since then, the Auschwitz Violin been played in concerts by musicians all over the world. Instruments like this one were very popular with Jews in Eastern Europe, as they were relatively inexpensive and made for amateurs. This particular violin was made in Saxony or Tirol in a German workshop by J.B. Schweitzer, who was a famous maker in his day. This violin is featured in Chapter 3 of James A. Grymes’ Violins of Hope.

The Heinrich Haftel Violin

Made by August Darte in Mirecourt, France, c. 1870

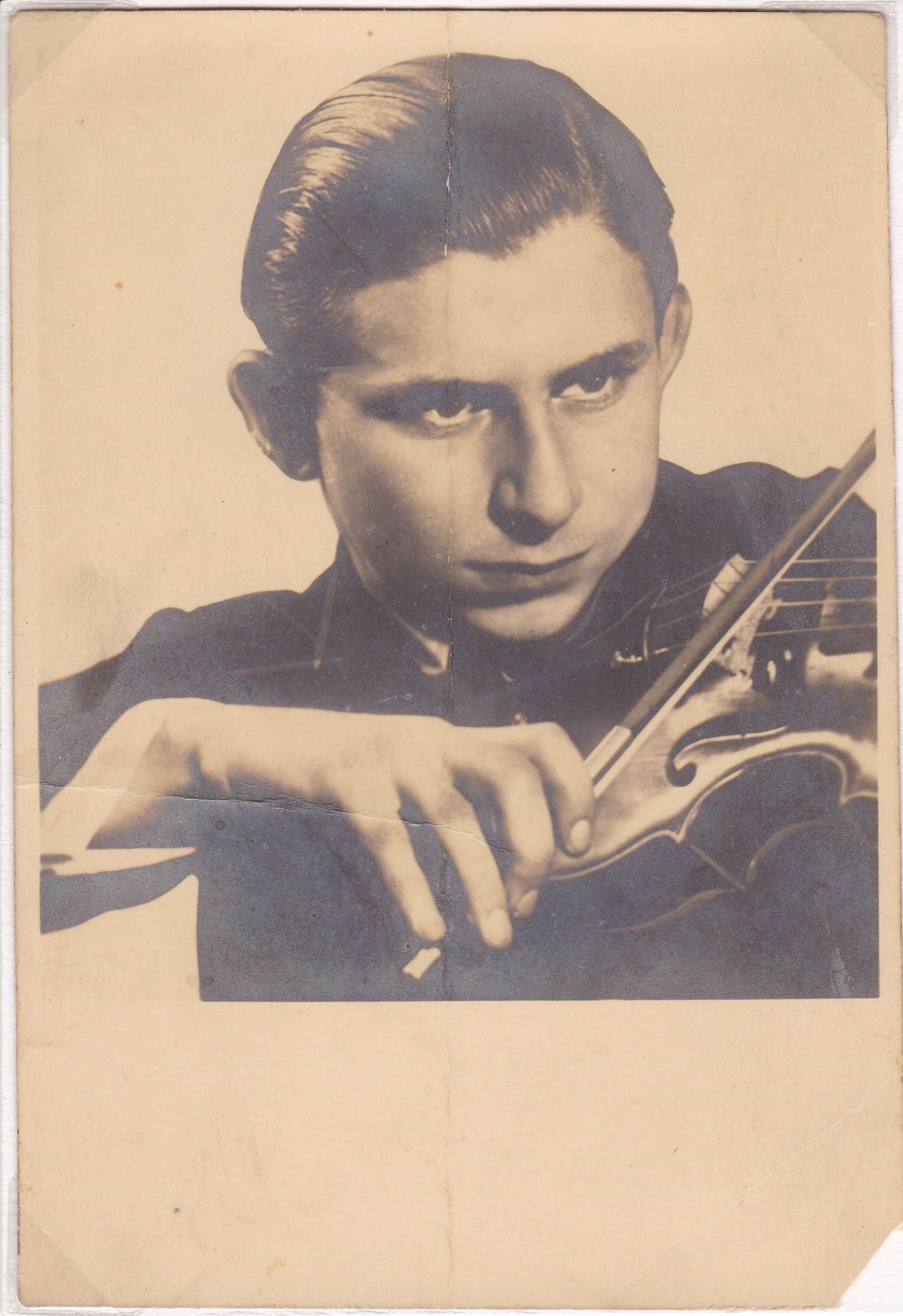

This violin belonged to Heinrich “Zvi” Haftel, the first concertmaster of the Palestine Orchestra. It is a French instrument constructed by the famous violin maker August Darte.

Haftel was one of about 100 musicians gathered by Bronisław Huberman from all over Europe in 1936 and brought to Palestine. He was a distinguished violinist before the war and joined Huberman after he lost his job in a German orchestra. Huberman’s vision to create an all-Jewish orchestra in Palestine saved the lives of many musicians and their families. Haftel’s violin is one of the finest in the Violins of Hope collection. This photo shows a gathering of original Palestine Symphony Orchestra members and their families.

The Shimon Krongold Violin

Warsaw, 1924

Shimon Krongold, a wealthy Jewish industrialist in Warsaw, bought this violin from Yaakov Zimmerman, who was possibly one of the first Jewish violin makers. The instrument is labeled, in Hebrew: “I made this violin for my loyal friend Shimon Krongold. Yaakov Zimmerman Warsaw 1924.” It also has a beautiful Star of David inlaid on the back.

Before the war, Krongold enabled Michel Schwalbé — who would later become concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic — to take violin lessons in the music room at his house. Later in his career, Schwalbé fondly remembered both Krongold and Zimmerman, the latter who gave him instruments and strings free of charge.

When World War II broke out, Krongold fled to the east and later died from illness in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Some years later, a person in possession of his violin came to the Krongold family home in Jerusalem, asking if they knew Shimon. Knowing it was their lost uncle, they bought his violin, one of the only surviving memories of him. In late 1999, Amnon gave a radio interview about the Motele Schlein violin. He asked listeners to contact him if they knew of any other violins connected to the Holocaust. The Krongold family brought Shimon’s violin to Amnon.

The biggest surprise came when Amnon peered into the violin and found a label that reads, in a combination of Hebrew and Yiddish, “This violin I made to commemorate my loyal friend Mr. Shimon Krongold, Warsaw 1924.” The dedication is signed by Yaakov Zimmerman, the same man who taught Amnon’s father how to repair violins more than 60 years earlier. The circle was complete. This violin is featured in the Epilogue of James A. Grymes’ book, Violins of Hope.

The Weichold Violin

Dresden, Germany, around 1910

Along with several others in the Violins of Hope collection, this fine, high-quality instrument belonged to a member of the Palestine Orchestra, created in 1936 by Bronisław Huberman. His vision to create an all-Jewish orchestra saved the lives of many musicians and their families because he was able to help them escape Europe during the rise of Nazism.

These instruments tell the story of the musicians who, after 1948, would become the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (IPO). Most members of the IPO were first-rate musicians who lost their positions in European orchestras when the Nazis came to power in 1933 and racial laws were enforced in Germany. Following the war, there was a general boycott of German goods in Israel, and even the word “Germany” was banned on the radio. Israeli musicians at this time refused to play on German-made instruments, and many came to Moshe Weinstein to request that he buy their violins.

“If you don’t buy my violin, I’ll break it,” some musicians said. Others threatened to burn their instruments. Weinstein bought each and every one because him the violin transcended war and evil. Yet he knew he would never be able to sell them.

The Moshe Weinstein Violin

Made by Johann Gottlieb Ficker, c. 1803

This violin was a lifetime friend of Moshe Weinstein, the father of Violins of Hope luthier Amnon Weinstein. Born in a shtetl in Eastern Europe, Moshe fell in love with the sound of the violin as a young boy. When a klezmer troupe arrived in the shtetl to play at a rich man’s wedding, he was hypnotized by the sound of music, while all the other children gathered under the table to hide and steal sweets. After a few festive days, the troupe left — and so did Moshe, who followed the klezmer musicians out of town.

Young Moshe was finally located and dragged back home, where he was first punished—and then given a very simple violin. This was a turning point in the Weinstein family history. He learned to play by himself and later studied at the music academy in Vilna (in present-day Lithuania), where he met Golda, a pianist. The two were married and in 1938 immigrated to Palestine.

Before leaving Europe, Weinstein traveled to Warsaw to study instrument building and repair with Yaakov Zimmerman. Since many Jews play the violin, he thought, they would need a violinmaker in the new land. After arriving in Palestine, he first worked in an orchard picking oranges and a year later opened a violin shop in Tel Aviv. Loyal to the tradition of assisting gifted young musicians pursuing music, Moshe supported many talented Israeli children, among them Shlomo Mintz, Pinchas Zukerman, and Itzhak Perlman.

The Klezmer Violin

The Violin with the Star of David

This lovely violin was originally made for a klezmer musician. The restoration work is dedicated to siblings Wolf and Bunia Rabinowitz, both gifted young violinists. They played multiple concerts in the Vilna ghetto during World War II, and were murdered with the last residents of the ghetto, most likely in the forest of Ponar, about 10 km outside the city.

The Freidman Hecht Violin

This violin belonged to a German woman, Fanny Hecht, whose family fled to the Netherlands in an attempt to escape the Nazis. There she befriended her neighbor, Helena Visser who sometimes played music with her. During the German occupation of the Netherlands, Hecht realized that her family would be taken by the Nazis, so she asked Visser to take care of her violin until she was able to return.

Visser crept into the Hecht family’s apartment — against her husband’s wishes — and retrieved the violin, which she then passed down to her children and grandchildren. Years later, the grandchildren learned of the Violins of Hope after watching a documentary on television late one night. Inspired by the project, they traveled to Israel, where they were able to learn the fate of the Hecht family — all of whom perished in concentration camps — and to deliver the violin personally to Amnon Weinstein.

“We’ve received a lot of violins in different ways,” Weinstein says. “Usually, it’s from relatives with whom the violin ended up, and they know it belonged to a relative who was killed in the Holocaust. Or it comes from people who have some interest in this musical memorial we are making. But with this Dutch family, this is the first time I’ve encountered such a story. It’s a good violin, German-made, valuable. It’s in excellent condition because it was hardly touched over the decades. The Visser family kept it for more than 70 years in order to keep their promise, and they wanted to return it to someone who will honor the memory of its legal owners.”

The Yaakov Zimmerman Violin (1920)

1920

This handmade violin is outstanding because of its unusually decorated five Stars of David, four on the face and one on the back. Usually made to order, these decorations were crafted from glue mixed with black powder.

This violin was found in very bad condition. The varnish was almost nonexistent, and it gave the impression of having been played most of the time in open air, rain or shine. It was meticulously repaired over the period of eighteen months and now serves as a concert quality instrument.

The Feivel Wininger Violin

Made by the Placht Brothers Workshop in Schönbach, Germany, c. 1880

Before the Holocaust, Feivel Wininger lived in Romania with his elderly parents, wife and baby daughter Helen. In October 1941, he and thousands of other Jews were deported by train to the swampland of Transnistria and further into Ukraine. The exodus was harsh, with much suffering and horror, but he never gave up. After settling in the Ukrainian ghetto of Shargorod, Wininger found a way to survive. A famous judge who also happened to be an amateur violinist recognized him as the gifted child-violinist he had seen years ago. The judge gave him his violin, which was made by one of the members of the famous Amati family in Cremona, Italy. Wininger, who labored chopping wood for local Ukrainians, played the violin, and his life changed. Now there was music — and hope.

A local Ukrainian peasant gave him opportunities to perform at weddings and holidays in exchange for food. Wininger lost his precious violin a short while later, but he found another, which gave him a way to continue performing Ukrainian and Romanian music. As a result, he was able to provide food for 17 family members and friends. Feivel immigrated to Israel, where he cherished the violin that had saved him and his family for the rest of his life. Many years later, Wininger’s daughter Helen brought her father’s violin to be repaired in the Weinsteins’ workshop in Tel Aviv, so that her now aged father could play again. Upon hearing his incredible story, the Weinsteins repaired the violin, which has since become a part of Violins of Hope and serves as a memorial to a man of courage, industry, vision and kindness. This violin is featured in Chapter 5 of James A. Grymes’ Violins of Hope.

The Bielski Violin

A German-made instrument, c. 1870

This violin was played by a klezmer musician. Music was one of the few art forms encouraged by Jewish tradition, and it was quite common for young children to play the violin.

Yiddish author I.L. Peretz wrote in one of his short stories that one could tell how many boys were in a Jewish family by counting the number of violins hanging on the wall. This is probably the reason so many klezmer instruments were decorated with the Star of David. Most klezmer violins were inexpensive, made in Czechoslovakia or Germany, in shops that specialized in ornamented violins.

Most klezmer players were self-taught musicians with natural talent, but this tradition was almost lost during World War II. Thanks to a new generation of musicians, there has been a klezmer revival in Europe, Israel, and United States. The restoration of this violin is dedicated to the Bielski partisans who fought and saved 1,230 Jews during the war. Assaela Weinstein, Amnon’s wife, is the daughter of Assael Bielski, one of the three brothers who formed the Bielski brigade in Belarus.

The Erich Weininger Violin

Made in the workshop of Schweitzer in Germany, c. 1870.

Erich Weininger was a butcher and amateur violinist in Vienna. When the Nazis invaded Austria in 1938, he was arrested and sent to Dachau, where he managed to bring his violin. Later, he was sent to Buchenwald, and though he was not allowed to play there, he still kept his violin. Miraculously, Weininger was released from Buchenwald with the help of the Quakers. He then returned to Vienna, only to be one of the very last Jews to escape Nazi Europe. He boarded a boat to Palestine, but was soon arrested by British police, who weren’t allowing Jews into the territory. With violin in hand, he was deported to the island of Mauritius off the coast of Madagascar, where he was interned until the end of World War II.

While in Mauritius, Erich was confined to the Beau Basin Prison where he and other refugee musicians formed a group called the Beau Basin Boys. The popularity of the Beau Basin Boys extended well beyond the prison walls. Their performances were broadcast over the radio and the musicians were allowed to leave the prison several times a week for performances that gave them their only moments of freedom. Erich died in 1988, at the age of 76. His violin was passed down to his son Ze’ev who in turn left it to his daughter, Tova. In 2012, Tova considered selling the violin and asked her son to take the violin to Tel Aviv to get it appraised. Her son quickly learned about Amnon Weinstein. The violin was damaged from being played outside in the Mauritius’s tropical heat and was not worth much; however, Amnon quickly recognized the instrument’s historical significance. He agreed to restore the violin for free. All he asked was permission to maintain Erich Weininger’s violin as one of the Violins of Hope. This violin is featured in Chapter 2 of James A. Grymes’ Violins of Hope.

The Jacob Hakkert Violin

Mirecourt, France, 1906

This is the first handmade violin by a famous Dutch-Jewish luthier, Jacob Hakkert, who studied in Mirecourt, in the north of France. He joined the family business in Rotterdam, Holland, ca. 1910, making violins, violas and cellos. He also had a reputation for developing and selling good-quality strings that were popular among many musicians. Sadly, Hakkert was deported to Auschwitz, where he died on May 22, 1944.

The Yaakov Zimmerman Violin (1929)

Warsaw, 1929

Yaakov Zimmerman worked in Warsaw and had many clients, both Jews and Christians. He was known to support young violinists, including Michel Schwalbé, who would later become concertmaster of the Berlin Philharmonic, and Ida Haendel, the child prodigy who became a world-renowned known virtuoso. Dated 1929, the violin was made by him for local clients.

The Moshe Amiran Violin

This violin wasn’t made by hand, but rather by machine. Although it looks like an authentic instrument, it doesn’t produce any sound. This type of violin usually belonged to beggars who made believe they played, but actually sang the music. Moshe Amiran, then a grandfather living in Israel, recalled the story of this violin and how it came to be in his possession: “From 1972-75, I lived in Santiago, Chile, where I met a man who survived the war and. found shelter in Chile. He was about 60 years old, spoke a broken Spanish typical to immigrants from Eastern Europe, and seemed rather lonely and poor. One day, he asked me to buy his old violin. I visited his home, where he showed me the number tattooed on his arm [indicating that he’d been in a concentration camp]. The man told me that the violin had belonged to his grandfather, who gave it to him and swore him to keep it, no matter what. In all his travels and troubles, he never parted with the instrument.”

“In 1942, the man was sent to a labor camp and then to Auschwitz-Birkenau, which he somehow survived with his violin. I paid him for his violin, feeling that I was doing a mitzvah [good deed]. As time went by, I put the violin away and forgot all about it. Three years later, I returned to Israel and discovered the violin inside one of my many crates. For a moment, I felt that the violin was following me so that one day it could tell its sad history.”

“Many years later, when my grandchildren grew up, I remembered the violin lying in the attic and decided to bring it to Amnon Weinstein in Tel Aviv. The rest is history, you may say. This violin does not play, but allows me to be poetic and sentimental and say that its silence is powerful, its silent strings touch hearts, and it is an authentic tombstone to many unknown and nameless violinists who died lonely and forgotten.”

The Heil Hitler Violin

This instrument is presumed to have been owned by a Jewish musician or an amateur who, at some point, needed a minor repair job. The craftsman doing the repairs opened the violin for no apparent reason and inscribed on its upper deck the words “Heil Hitler, 1936,” alongside a swastika. He then closed the violin case and handed it back to the owner, who played it for years, unaware of the inscription.

Recently, the violin was bought by a violin maker in Washington, D.C., who was astonished to discover the secret obscured inside. The maker’s first instinct was to burn the instrument, but on second thought he contacted the Weinsteins in Tel Aviv and donated it to the Violins of Hope project.

Today, it is part of the collection, but it will never be repaired or played. It is important to note that the majority of German violin makers were not Nazis. Many were known to support Jewish musicians whom they considered devoted clients and friends.

The Wedding Violin

The Sandor Fisher Violin

This violin tells the story of two Holocaust survivors. Born in Hungary in 1925, Valeria Teichner began violin lessons at age 6. In 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz. When boarding the cattle train to the camp, she forgot her violin. Upon disembarking, she went through a “selection,” where she lost her mother and was sent to the music barrack. In tears and unable to play, she was sent to the laundry barrack, only to endure another “selection.” From there, she was sent to Gorelitz, another hard-labor camp, where she worked in a munitions factory. The sadistic capo (a prisoner forced to supervise work details) used to play his violin every evening. He played well, she said.

On Christmas Eve, all prisoner-musicians were ordered to play and sing for the commanders. Teichner was among those musicians and sang “Lorelei,” accompanying herself on the violin. The next day, the officers’ cook threw her a piece of cake over the fence — a terrible crime. The capo sentenced her to be hanged in Gross-Rosen, the main camp. When the car came for her, the capo called out: Geigerin heraus! (“Violinist–out!”). He then changed his mind, hit her in the face, and let her stay. She was liberated by the Soviets on May 8, 1945.

Teichner soon met Sandor Fisher, the owner of this violin, and married him. He was born in 1919 in Romania, where he began violin lessons at age 6 and studied singing and acting for 12 years. At 18, he changed his name to Farago Sandor to avoid persecution as a Jew, and became part of the local opera company. When the situation for Jews worsened and his father was conscripted to hard labor, Fisher went to the work camp, accompanied by his violin. Soon he was ordered to play for the officers during dinner and was able to smuggle leftovers for his friends.

In 1944, Fisher managed to escape the labor camp and joined the Soviets. After the war, he married Valeria Teichner, and the couple remained in Hungary until immigrating to Israel. They raised a family of three daughters, along with grandchildren and great- grandchildren. His daughters relayed that Sandor never parted with his violin, and he played it to the end of his days.

The Morpurgo Violin

Several years ago, a woman in her 90s, Signora Morpurgo, came with her three daughters to the Weinsteins’ workshop in Tel Aviv. They brought with them the treasured violin of her husband, Gualtiero Morpurgo.

The Morpurgos are a respected Jewish family whose roots go back 500 years in the north of Italy. When he was a young child, Gualtiero’s mother handed him a violin and said: “You may not become a famous violinist, but the music will help you in desperate moments of life and will widen your horizons. Do not give up. Sooner or later, it will prove me right.”

That moment arrived without warning. At the Central Station in Milan, Gualtiero’s mother was forced to board the first train to Auschwitz. Gualtiero was sent to a forced labor camp and, loyal to his mother, took the violin with him, often finding hope and strength while playing Bach’s Partitas with frozen fingers after a long day’s work in harsh conditions.

A trained engineer who worked in the shipyards of Genoa, Morpurgo volunteered his engineering skills after the War to build and prepare ships for Aliya Bet, the code name given to the clandestine immigration by Jews, most of whom were Holocaust survivors and refugees from Nazi Germany. For this violation of the restrictions laid out in the British White Paper of 1939 Gualtiero was awarded the Medal of Jerusalem by Yitzhak Rabin in 1992.

Throughout his life, Gaultiero never stopped playing. He was 97 when he closed the case on his lifelong companion. After his death in 2012, his widow and their three daughters attended a Violins of Hope concert in Rome where they decided to donate his instrument to the Violins of Hope project.

The Friedman Violin

Two sisters, aged 9 and 11, shared the same violin. Both took music lessons while their mother watched over them and ensured their studies. During the war, as they were transported from one place to another, they were separated from their parents, who kept the violin as a constant reminder of their talented daughters.

When the war ended, the girls were taken by Aliyat HaNoar, the Jewish children’s immigration organization, and sent by boat to Palestine. British police, then in control of the territory, sent the boat and all immigrants aboard to a camp in Cyprus. The sisters were reunited with their parents and their violin when they arrived in Israel with thousands of other Holocaust survivors who were interned in Cyprus until the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948.

The Berlin Gypsy Violin

On January 27, 2015, International Holocaust Day, the Berlin Philharmonic held a concert celebrating the Violins of Hope. Sponsored by Frank-Walter Steinmeier, then the Foreign Minister of Germany, the concert marked 70 years since the liberation of Auschwitz by the Soviets. On that day, the Violins of Hope received an instrument with a unique history: Donated by Sabine Conrad, a young German woman, the violin had been given to her many years before by Erich Winkel, an 80-year-old Communist.

Conrad had been Winkel’s caretaker, and he gave her his beloved violin as a token of gratitude and appreciation. He bought the violin from a Gypsy when he played in the Communist youth orchestra. The ensemble used to play in the early 1930s in north Berlin and was often attacked by the Nazis, even before they came to power. Winkel was very proud of his instrument, which he said survived many ferocious attacks by Nazi hoodlums.

The Dachau Violin

This violin belonged to Abram Merczynski. In August 1944, he and his two brothers, Isak and Zysman, were deported from the ghetto in Łódź, Poland to Auschwitz and then to Dachau. Abram was 21 years old and played his violin wherever he was, even in Kaufering, a sub-camp of Dachau. He and his brothers survived, as did his violin. Before they immigrated to the United States in 1955, the three brothers rented a room with the Sesar family in Munich.

Merczynski soon bought himself a new violin and gave his old instrument, which had accompanied him through all his troubles, to the young Julius Sesar, then 14 years old. He lived to be 88, and his daughter Eleanor said he never stopped playing the violin. Julius Sesar, now an old man himself, gave Merczynski’s violin to a friend, Eberhard Thiessen, a violinmaker who in turn donated it to the Violins of Hope project, so that the violin will continue to be played and tell stories of survival, music and friendship.

The AIPAC Violin

This violin belonged to Dr. Leon Schatzberg-Sawicki, born in 1918 in the town of Kolomyia, then part of Poland and now Ukraine. He graduated from the Lviv Conservatory in 1938 and studied medicine at Lviv University, graduating in May 1941. He married a fellow student, Ella Schrenzel. During the Nazi occupation, he changed his name to the Polish, Sawicki, with the help of false identity papers. He played this violin all over Poland on street corners, in restaurants, and in impromptu bands, while Ella tutored Polish children. They were liberated by the Soviets in July 1944. Both lived long lives with children and grandchildren.

The Buried Violin

Heinrich Herrmann was born and raised in Schwabach and Nuremberg, in the south of Germany, where he learned to play the violin. He studied law and became a judge, but following the Nuremberg laws, lost his position because of his Jewish identity. He then fled to Amsterdam, where he became a typewriter salesman and met his wife, Ilse. Heinrich clung to his old, inexpensive Gypsy violin and often played chamber music with friends. In the mornings, he tried to secure a visa to Cuba or any other country that would offer them a chance to leave Europe. With this plan in mind, he used all his savings to buy a 150-year-old instrument handmade in the famous atelier of the Klotz family in Bavaria, Germany.

Herrmann thought that once he immigrated to Cuba, he could sell the extraordinary violin to support his family. His plan was thwarted when all Jews in Holland were forced to register with the Nazi police and surrender all their valuables. He brought his violin and told the clerk that he had no problem giving away all his valuables, but could not part with his violin. “Go home with your violin,” said the clerk, “and come back tomorrow with another. But don’t tell anyone I said so.”

The Herrmanns asked a Dutch friend, Yan Molder, to keep the violin. On June 23, 1943, they were imprisoned by German police and sent to Bergen-Belsen. Molder was afraid the Nazis would find out that he had held on to Jewish property, so he gave it for safekeeping to a musician friend, who also feared the police and buried the violin in his Garden.

Miraculously, Heinrich and Ilse Herrmann survived, and in 1944 they were exchanged for German citizens being expelled from British-held Palestine. A year later, after the end of the war, the violin, now badly damaged, was brought to them in Palestine. It was repaired and stayed close to Heinrich, who played it for the next 40 years.

The Lyon, France Violin

Made in Germany, c. 1900

In July 1942, thousands of Jews were arrested in Paris and sent by cattle trains to concentration camps to the east, most to Auschwitz. On one of the packed trains was a man holding a violin. When the train stopped somewhere in the middle of France, the man heard voices outside the train car. A few men were working on the railways.

The man in the train cried out, “In the place where I’m going now, I don’t need a violin. Here, take my violin so it may live!”

The man threw his violin out the narrow window. It landed on the rails and was picked up by one of the French workers. For many years, the violin had no life. No one had any use for it. Years later, the worker passed away, and his children found the abandoned violin in his attic. They tried to sell it to a local maker in the south of France and told him the story they had heard from their father. The French violin maker, in turn, gave the instrument to the Violins of Hope project so that the violin could live.

The German Violin

Played by Shlomo Mintz

This violin clearly survived the Jewish fate – either a ghetto hard labor camp or worse. The identity of the owner is unknown. The instrument is featured in the documentary film Le Voyage d’Amnon (Amnon’s Journey), played by the great Israeli violinist Shlomo Mintz. When Mintz performed Ernest Bloch’s “Ba’al Shem” at the gate to Auschwitz, the violin had in effect come full circle, returning to the very place where it had once been played.

Photo Credit: Irma de Jong and Yonathan Weitzman

The German Star of David Violin

c. 1890

This is the most beautiful klezmer violin in the Violins of Hope collection, a first-class handmade instrument that dates to the late 19th century. It was most likely owned by a wealthy klezmer musician, as it appears to have been more expensive than most klezmer instruments. The Star of David is made of mother of pearl.

The American Soldier Violin

The reconstruction of this violin is dedicated to the memory of the American soldiers who alongside other Allies fought against the Nazis, all those who died so that others could live free.

The Viola by Carl Zach

Vienna, 1896

This is the only viola in the Violins of Hope. It belonged to a member of the Palestine Orchestra.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)